Tell us what you do at the City of Amsterdam.

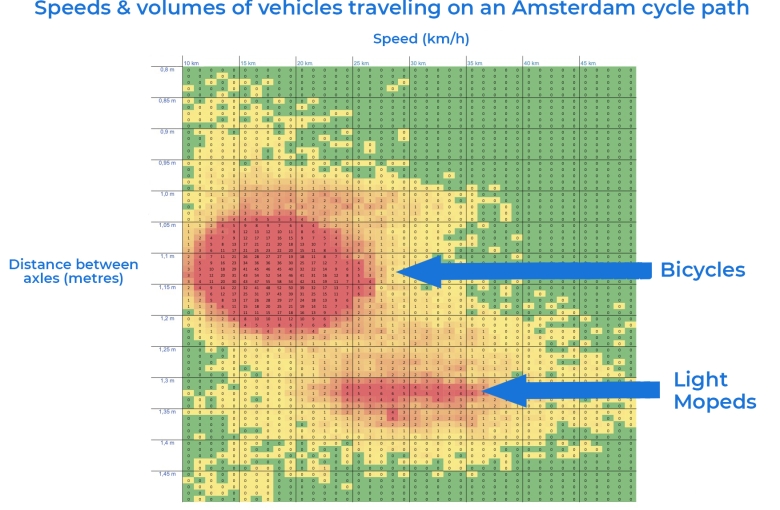

I am a researcher at the Traffic & Public Space Department. I am involved in policy evaluation studies and monitoring, among other things. An example of this is the recent survey we completed using MetroCount systems to determine if light mopeds should be removed from Amsterdam's cycleways.

In addition to encouraging cycling, the facilitation of sufficient bicycle parking space is also a challenge here. In the districts further from the centre, where there is more space, the challenge is to get people to cycle more.

Compared to vehicle traffic, we still have little real-time insight into cycling volumes, the routes cyclists take and why they do so.

How does having cycling data help you to overcome these challenges?

Devising new policies and infrastructure all starts with data. We work “evidence-based” as much as possible, to ensure decisions are based in reality and are measurable. We consider volumes of cyclists and other modalities, along with origin and destination information. The data is used as input for our traffic modelling.

What are some of the challenges involved in traffic planning for cyclists in Amsterdam?

The challenge lies mainly in facilitating cycling in parts of the city where space is the most scarce.

How do we ensure sufficiently wide cycle paths and logical routes to handle large numbers of cyclists safely? This is the case in the old centre and the surrounding neighbourhoods.

Car use is being limited by the introduction of low-traffic measures and the removal of car parking spaces in the street. But loading and unloading, for example, must still remain possible. There must also be sufficient space for another vulnerable road user: the pedestrian.

In addition to encouraging cycling, the facilitation of sufficient bicycle parking space is also a challenge here. In the districts further from the centre, where there is more space, the challenge is to get people to cycle more.

Compared to vehicle traffic, we still have little real-time insight into cycling volumes, the routes cyclists take and why they do so.

How does having cycling data help you to overcome these challenges?

Devising new policies and infrastructure, all starts with data. We work “evidence-based” as much as possible to ensure decisions are based on reality and are measurable. We consider volumes of cyclists and other modalities, along with origin and destination information. The data is used as input for our traffic modelling.

Monitoring cycling. Do you collect your own cycling data?

We collect our own cycling data through an extensive counting program. We also monitor parked bicycles. In addition, we participate in initiatives such as Fietselweek (bicycle counting week), which also provides us with app data from cyclists themselves and their routes. But as I said before, we have little data on bicycles compared to cars.

What sort of cycling data do you find most beneficial (e.g. app data, manual counts, automatic bike counters etc)?

The most ideal is a combination of automated count data and movement data via apps so that you have information about trends at specific locations around the city and information about the routes that people take.

In your opinion, what are the pros and cons of each counting method?

Choosing the right method depends on your demand and budget. You can often do a lot with camera data, but this is also expensive and has privacy issues. A pneumatic tube counter is often sufficient, as it gives a good picture of the traffic intensity at a certain location.

The big advantage of tube counters compared to loop counters is that they are flexible, cheap, and easy to install for a short period of time. If you want to measure permanently, a counter in the road is more attractive. Tube counters are also less sensitive to vandalism or damage from traffic (for example, road sweepers).

App data is great, but you depend on whether people want to use the app and whether the data can be shared.

Tell us why the City of Amsterdam banned light moped use on cycle paths.

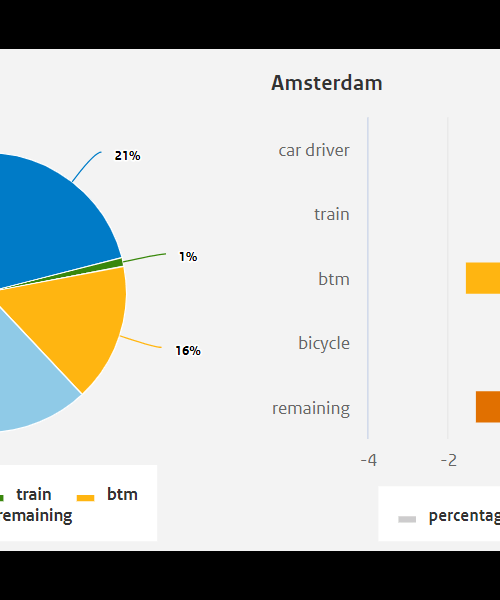

Until April 2019, moped riders were required to ride on the cycle path, not the road. This caused conflicts on the increasingly busy (and often narrow) cycle paths. There was also a large speed difference between light mopeds and cyclists, leading to a relatively high number of road accidents involving mopeds. It was decided to move the moped to the roadway (with helmets mandatory) within the A10 ring road of Amsterdam.

What data was used to help inform this decision?

Various studies and pilots preceded the decision to move the moped to the roadway. This included monitoring volumes and speed of each mobility type, but also the number and type of conflicts and the perception of the different road users. The decision itself was also evaluated with a zero measurement, a 1-measurement and a 2-measurement, during which, among other things, compliance with the new rules was monitored.

What have been the outcomes of moving light mopeds on the roads?

The main outcome is that the number of accidents involving light-moped riders has fallen sharply. Cyclists’ user experience of cycle paths has also improved as they feel safer and enjoy a more pleasant journey overall.

The opinions of light-moped riders themselves are split. A side effect is that the number of light-moped riders in the city has decreased since the measure was introduced. Some users have switched to higher-powered mopeds, while others have chosen a different way of getting around altogether.

What other big decisions have been made recently by cycling data?

Data is constantly being used to support more space for bicycles. For example, Amsterdam’s inner ring (the route north of the Singelgracht: Sarphatistraat-Weteringschans-Marnixstraat) will be converted into a bicycle boulevard.

Bicycle and public transport have priority here, the car is a guest. Bottlenecks for cyclists are solved and missing links are added to create a logical and attractive cycling route.

Why is it so important to have up-to-date cycling data?

Amsterdam is a cycling city. It has the largest transport mode share among Amsterdammers (in number of trips). As a municipality, we want to continue to facilitate this. Cycling is a healthy and clean mode of transport that suits the city. Monitoring usage to base or fine-tune our policy is an important task to ensure that Amsterdam remains a pleasant cycling city.

Thanks, Maarten, for your insights into the challenges and opportunities of monitoring cycling in Amsterdam.

Got a great MetroCount story? Share it with us and let the world know the great work you're doing in your community.